It has felt, at times, that my development as a photographer has been akin to a layering up of visual experiences. Over time I’ve become more aware and sensitised to my environment – it’s an offshoot of working in a visual field.

Lichen holds a particular fascination for me as an architectural photographer. I find them on most surfaces of the buildings that I photograph, and I’m starting to see a logic to their whereabouts. Some lichens are particular to the surfaces they inhabit and others thrive in the light or shade.

A lichen, as I understand it, isn’t one thing or another, but the product of a harmonious relationship between two things: a symbiosis between algae and fungi. One can’t live without the other.

Lichens confound the idea that species need to compete to progress. They are living examples of mutual cooperation. It is thought that lichens may have been the instigators of the development of complex life forms millions of years ago – that they may have populated our earth from a meteorite, introducing a key ingredient that created new life. To this end, lichens have been transplanted onto rocket surfaces to understand their role in our evolution.

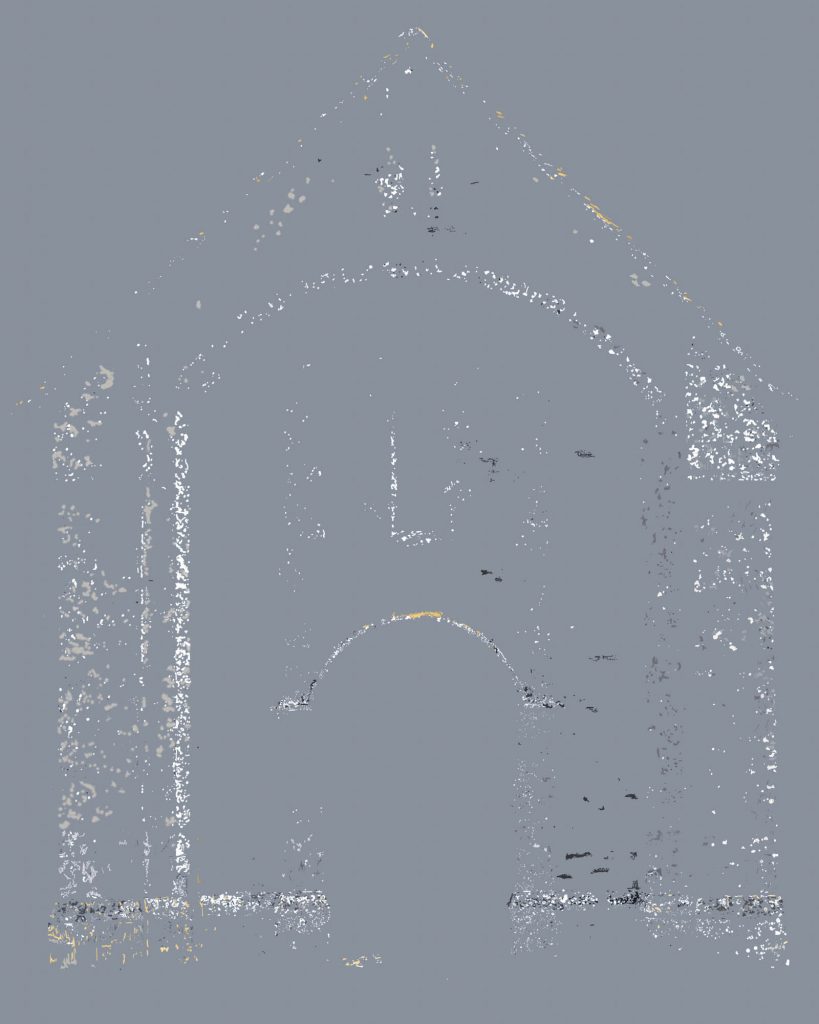

Every now and then I’ve come across a kind of bioluminescence caused by lichen and fungi that thrive in dark conditions.

Bioluminescence on Roman stonework in the crypt at Hexham Abbey

On one occasion, for the briefest of moments I saw a flash of light from lichen at dawn on the facade of a church and I created a lichenograph to share what I saw.

"As the harmonious relationship between people and their houses is called a home, the symbiosis between algae and fungi is called a lichen. One can't live without the other. "

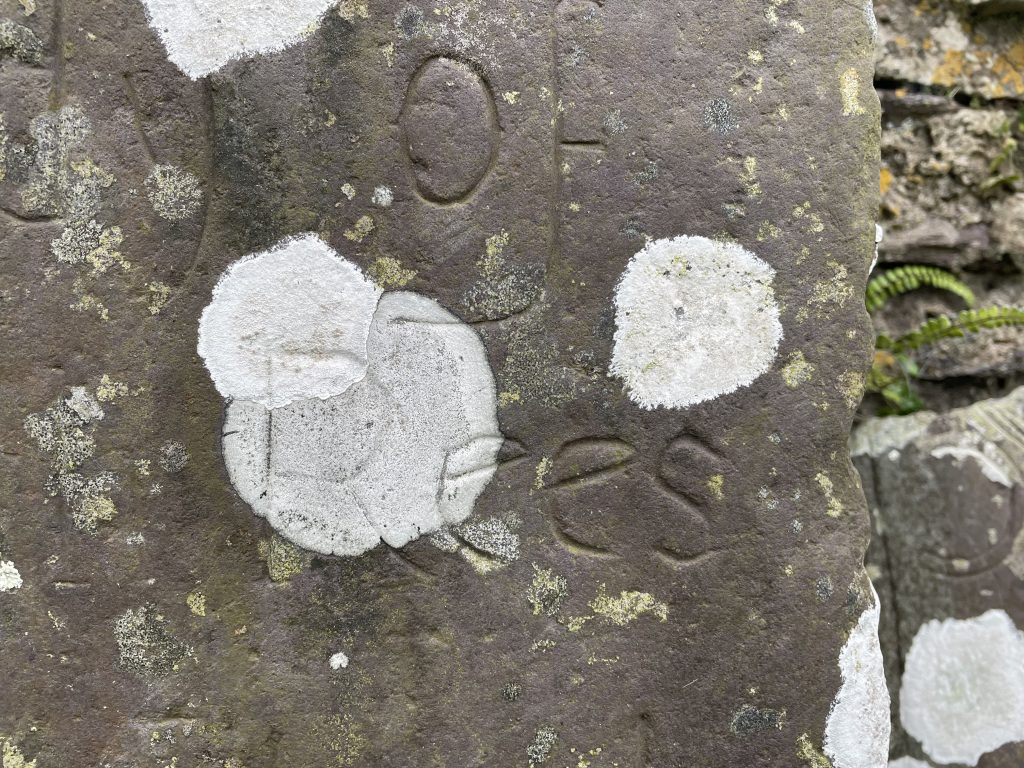

Photographing Lichen

I use a tripod to take several photos of the lichen with a macro lens on manual focus. Each photograph is taken with different depths of focus. I use Photoshop to ‘focus stack’ the images – so that the final image is pin sharp. The above image of a Permelia lichen was taken this way and is available as a digital print.